A Tree Beyond Flowers and Seeds

Across India’s dry deciduous forests, the Mahua tree (Madhuca longifolia) stands as one of nature’s most generous companions. Its fragrant flowers are celebrated for food and fermentation, while its seeds yield oil used in lamps, soaps, and rural kitchens. Yet, beyond these well-known gifts, the tree hides another dimension—its leaves and fruits quietly sustain livestock that form the heartbeat of rural livelihoods.

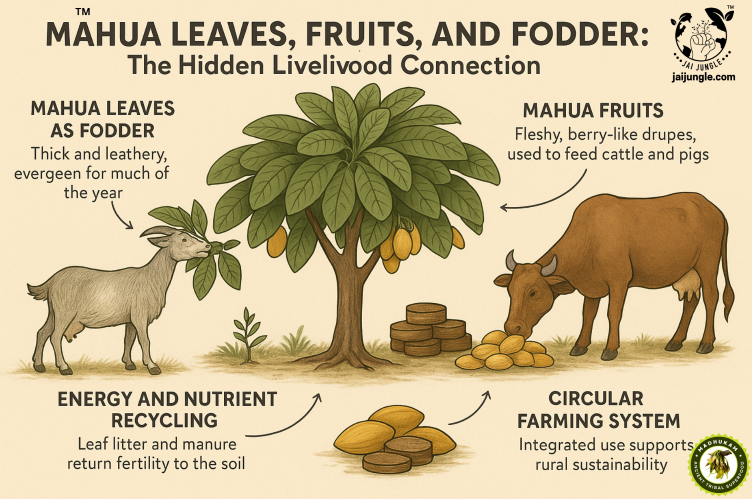

In traditional farming systems, nothing from Mahua goes to waste. Leaves feed goats and sheep; fruits nourish cattle and pigs; seeds provide oil; and the remaining seed cake fertilizes fields. Fallen leaf litter enriches the soil with organic carbon and minerals. This entire chain creates a natural model of circular agriculture—an approach modern sustainability science now strives to replicate.

According to World Agroforestry (ICRAF, 2019), regions with dense Mahua stands report greater fodder security, especially in drought years. The tree remains semi-evergreen in moist regions and stays green longer into the dry season in drier belts—providing crucial green matter when grasses vanish. For many families, the Mahua tree stands as a silent provider, ensuring food for people, feed for animals, and fertility for the soil.

Mahua Leaves as Fodder: A Seasonal Lifeline

Mahua leaves are thick, leathery, and oval-shaped, typically 10–20 cm long, with a slightly glossy surface. In semi-humid zones, the tree is nearly evergreen, shedding briefly before flowering. In drier areas, it behaves as a deciduous species—yet even then, leaves persist through critical fodder-scarce months.

Traditional Feeding Practices

Livestock keepers across central and eastern India have long recognized the fodder value of Mahua leaves. Goats and sheep relish the tender leaves and small twigs, while cattle occasionally browse on the fallen ones. During droughts, when grasslands turn barren, Mahua leaf fodder has saved countless herds from starvation.

Women, often the primary livestock managers, collect green leaves or break small twigs daily for their goats (ICRAF, 2019). The animals not only eat them readily but maintain milk production and body condition better than those fed only dry crop residues. Farmers frequently remark that “Mahua patta bina bakri kamzor lagti hai” (without Mahua leaves, goats grow weak).

Nutrient Composition of Mahua Leaves

The nutritional value varies by season and soil type, but multiple analyses show Mahua leaves are a moderate-quality fodder with adequate protein for maintenance diets:

| Nutrient Component | Approximate Value (Dry Basis) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Crude Protein | 10–12% | Comparable to subabul or acacia leaves |

| Crude Fiber | 18–20% | Moderate digestibility for goats and sheep |

| Calcium | 1.1–1.3% | Good for bone health and milk production |

| Phosphorus | 0.25–0.30% | Sufficient for metabolic balance |

| Potassium | 0.9–1.2% | Helps maintain body fluid balance |

| Metabolizable Energy | 6.5–7.0 MJ/kg DM | Moderate energy fodder |

(Source: National Institute of Animal Nutrition and Physiology, Bangalore; ICRAF Fodder Database, 2019)

In practical terms, these values mean that Mahua leaf fodder can supplement low-protein feeds like straw, improving animal health and productivity.

Farmer Perceptions and Ranking

In a multi-state survey on agroforestry trees used for fodder, farmers ranked Mahua among the top five fodder trees for its availability and drought resilience (University of Kentucky Agroforestry Survey, 2017). Its leaves, though coarser than leguminous fodder, are preferred because they remain accessible year-round and do not require irrigation or fertilizer inputs.

Mahua Fruits: From Forest Floor to Feed

Mahua fruits appear as oval drupes (3–5 cm long), green when immature and turning yellowish upon ripening between May and July. Inside each fruit lies the hard seed that yields Mahua oil. The fleshy fruit pulp, however, is often overlooked as a powerful livestock energy source.

Traditional Use of Fruit Pulp

Once ripe fruits fall to the ground, villagers collect them. The seeds are removed for oil extraction, and the leftover pulp is mashed or sun-dried for animal feed. Farmers feed the pulp to cattle, buffaloes, and pigs. According to 101Reporters (2022), in several tribal villages of Maharashtra and Jharkhand, pigs are deliberately allowed to roam under Mahua trees during fruiting season—naturally fattening on fallen fruits without external feed costs.

The pulp, rich in starches and simple sugars, provides a natural energy supplement similar in caloric value to cereal grains.

Nutrient Profile of Mahua Fruit Pulp

| Component | Approximate Value (Fresh Basis) | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 65–70% | High water content; perishable |

| Carbohydrates | 24–28% | Energy source similar to potato |

| Crude Protein | 2–3% | Low, requires supplementation |

| Crude Fat | 0.8–1.2% | Minor lipid contribution |

| Fiber | 3–4% | Aids digestion |

| Ash (minerals) | 1.2–1.5% | Supplies micronutrients like potassium |

(Source: BSMIAB Journal, 2020; ICAR Feed Resource Bulletin, 2021)

Farmers often mix sun-dried Mahua pulp with chopped straw and oilseed cakes, creating a cost-effective feed blend. Such integration lowers feed costs and recycles forest biomass into the farm nutrient loop.

Seed Cake: From Oil Extraction to Organic Fertilizer

The Mahua seed cake, left after oil extraction, is another crucial by-product. It contains roughly 14–16% crude protein but also natural saponins and tannins, making it mildly toxic if fed raw. Traditional farmers, however, detoxify it by boiling or soaking in water for 24–48 hours, then drying it before feeding to livestock (ICAR, 2018).

In regions where feeding is avoided, farmers spread the cake directly on fields as organic fertilizer. The cake releases nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium gradually, improving soil fertility. Studies from the Indian Institute of Soil Science (2020) show that 1 ton of Mahua cake can add up to 35 kg of nitrogen equivalent to the soil, reducing dependence on synthetic urea.

Thus, whether as feed or fertilizer, the seed cake returns nutrients back to the ecosystem, closing Mahua’s sustainable loop.

Energy and Nutrient Recycling: A Natural Closed Loop

The integration of Mahua into the farming system illustrates how traditional agro-ecosystems achieve circularity without external inputs.

- Leaves → feed for goats and sheep

- Fruits → feed for cattle and pigs

- Seeds → oil for domestic and economic use

- Seed Cake → feed or fertilizer

- Leaf litter and manure → soil organic matter

This sequence ensures that energy captured by Mahua through photosynthesis flows through multiple trophic levels—from plant to animal to soil and back again.

According to World Agroforestry (ICRAF, 2019), integrating fodder trees like Mahua into mixed farming systems can increase on-farm biomass productivity by 25–30%, reduce feed shortages, and enhance soil carbon storage by up to 1.2 tons/ha/year.

Ecological Benefits: Soil, Carbon, and Water

Beyond fodder and food, Mahua provides important ecosystem services that make it an environmental asset.

- Soil Conservation: The dense leaf litter adds organic matter, improving water infiltration and reducing erosion (IISS, 2020).

- Carbon Sequestration: Mature Mahua trees can store 3.5–4.0 tons of carbon per hectare annually, helping mitigate climate change.

- Microclimate Regulation: The broad canopy provides shade and reduces local temperature extremes, creating favorable conditions for understory grasses and herbs.

- Pollinator Habitat: Mahua’s long flowering season supports bees, bats, and insects crucial for pollination.

These ecological roles enhance farm resilience, ensuring productivity even under climatic stress.

Other Traditional Uses of Mahua Leaves

Mahua leaves, beyond their fodder function, have diverse cultural and utilitarian roles:

- Leaf Plates and Bowls: In several central Indian villages, dried Mahua leaves are stitched into eco-friendly plates (pattal) and bowls (dona). Though less common than sal leaves, they serve as sustainable alternatives during local festivals and rituals.

- Medicinal Applications: Ethnobotanical surveys (ResearchGate, 2021) report that warm Mahua leaves are used as poultices to reduce joint inflammation and swelling, owing to their mild anti-inflammatory and emollient properties.

- Mulch and Biomass Fuel: Dried leaves are used as mulch for moisture retention or as fuel for quick fires in rural kitchens.

- Bee Fodder Support: During flowering, fallen leaves provide organic mulch that supports soil organisms, indirectly aiding pollination ecology.

Mahua and Wildlife: A Shared Resource

Mahua’s ecological generosity extends to the wild. Deer, wild boar, monkeys, and sloth bears feed on fallen flowers and fruits. According to the Wildlife Institute of India (2018), Mahua fruits constitute up to 15% of the sloth bear’s seasonal diet in central Indian forests.

Farmers often leave a portion of the crop uncollected—an act not of negligence but of coexistence. By sharing part of the forest yield, they reduce crop raids and maintain ecological harmony. Such community ethics reflect the indigenous understanding of balanced harvesting.

Economic Significance in Rural Systems

While Mahua leaves are rarely traded commercially due to their bulkiness and low shelf life, their indirect economic contribution is substantial. Healthy livestock provide milk, manure, and draught power—key components of rural income and security.

The fruit pulp, when dried, has emerging potential in local markets as a feed ingredient. Pilot studies by the National Dairy Development Board (2022) found that incorporating 10–15% dried Mahua pulp into cattle feed reduced total feed costs by 12–15% without affecting milk yield.

In this way, Mahua represents an unrecognized economic buffer—supporting livestock, which in turn sustains household economies.

Sustainable Harvest and Regeneration

Mahua’s regeneration depends on balanced use. Overharvesting leaves or collecting every single fruit can hinder its natural reproduction. Traditional communities have long understood this balance.

- Leaf Harvesting: Families pluck selectively, avoiding complete stripping. Many simply gather fallen green leaves, ensuring photosynthetic recovery.

- Fruit Harvesting: Some fruits are intentionally left behind for wildlife or natural germination.

- Community Protocols: In certain tribal belts of Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand, local norms restrict lopping branches during flowering or fruiting months—demonstrating ancient conservation wisdom.

Sustainable harvesting ensures that Mahua continues to thrive, supporting biodiversity while providing livelihood benefits year after year.

Integration into Farming Systems

The integrated use of Mahua aligns perfectly with modern concepts of agroforestry and permaculture. A typical rural system follows this natural rhythm:

Flowers → food, syrup, or fermented beverages

Seeds → oil for lamps and cooking

Seed Cake → fertilizer for crops

Leaves → fodder for goats and sheep

Animals → manure and milk

Manure → fertile soil, feeding the next cycle

This closed-loop demonstrates how Mahua sustains entire farming systems without synthetic inputs, embodying sustainability through practice rather than theory.

Research and Policy Perspectives

Recent research has begun to quantify Mahua’s importance in India’s livestock-feed balance. According to ICAR (2023), India faces a green fodder deficit of 35–40% annually. Integrating multipurpose trees like Mahua could offset this shortage significantly, especially in semi-arid regions.

Policy frameworks under the National Agroforestry Policy (2014) and National Livestock Mission (2022) encourage the inclusion of native fodder trees in farm systems. Recognizing Mahua under these programs could link traditional knowledge with scientific planning, ensuring long-term sustainability.

Furthermore, with growing interest in carbon farming and payment for ecosystem services, farmers maintaining Mahua trees could potentially receive carbon credits for sequestration and soil health contributions—opening new livelihood pathways.

Lessons from Traditional Ecology

Long before sustainability became a buzzword, rural communities practiced it instinctively. Mahua exemplifies this living wisdom. The tree’s presence near villages reflects deep ecological integration—every household using it, yet none depleting it completely.

This decentralized stewardship model—where each family protects “its” Mahua tree—ensures continuity without central enforcement. It is, in essence, community-based resource management in action.

Conclusion

The story of Mahua leaves and fruits as fodder is not just about animal feed—it is about interdependence. Humans, livestock, soil, and forest all form one continuous chain of life supported by this remarkable tree.

By nourishing goats and cattle, fertilizing soil, and offering shade and nectar, Mahua sustains both economy and ecology. It represents a living circular economy, rooted in indigenous knowledge and validated by modern science.

Recognizing these multiple values can shift the perception of Mahua from a liquor-producing tree to a keystone species for rural resilience—a pillar of India’s agroecological heritage.

Quick Reference Summary

| Function | Beneficiary | Key Benefit | Sustainability Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Goats, sheep | Green fodder during lean season | Drought resilience |

| Fruits | Cattle, pigs | Energy-rich feed | Nutrient recycling |

| Seeds | Households | Oil for cooking and lighting | Income generation |

| Seed Cake | Soil or animals | Fertilizer/feed | Reduces chemical inputs |

| Leaf Litter | Soil microbes | Organic matter enrichment | Carbon sequestration |

References and Data Sources

- World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF). (2019). Agroforestry Tree Database: Madhuca longifolia. Nairobi, Kenya. Available at: https://apps.worldagroforestry.org

- National Institute of Animal Nutrition and Physiology (NIANP). (2019). Feed and Fodder Composition Tables for Indian Livestock. Bengaluru, India.

- University of Kentucky. (2017). Farmer Preferences and Utilization of Fodder Trees in South Asia: Agroforestry Survey Results. Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Lexington, KY, USA.

- BSMIAB Journal. (2020). Proximate Composition and Nutritional Analysis of Mahua (Madhuca longifolia) Fruit Pulp. Bangladesh Society for Microbiology and Industrial Applications Bulletin, Vol. 8(2), pp. 44–52.

- Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR). (2018). Traditional Detoxification and Nutritional Evaluation of Mahua Seed Cake for Livestock Feed. Feed Resource Bulletin, ICAR-NIANP, Bengaluru.

- 101Reporters. (2022). How India’s Forest Communities Sustain Livelihoods through Mahua Tree Products. https://101reporters.com

- Indian Institute of Soil Science (IISS). (2020). Organic Manure and Biomass Recycling Potentials of Mahua Seed Cake in Central India. Bhopal, India.

- ICAR-National Dairy Development Board (NDDB). (2022). Pilot Studies on Integration of Non-Conventional Feed Resources in Cattle Diets. Anand, Gujarat.

- ResearchGate. (2021). Ethnomedicinal Applications of Madhuca longifolia Leaves among Central Indian Tribal Communities. Available at: https://researchgate.net

- Wildlife Institute of India (WII). (2018). Feeding Ecology of Sloth Bears in Central India with Special Reference to Mahua Fruit Consumption. Dehradun, India.

- Indian Institute of Soil Science (IISS). (2020). Soil Organic Carbon Accumulation under Native Tree Species in Semi-Arid Tropics of India. Bhopal, India.

- Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR). (2023). India’s Fodder and Feed Balance Report: Challenges and Strategies. ICAR-IGFRI, Jhansi.

- National Agroforestry Policy. (2014). Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Government of India.

- National Livestock Mission (NLM). (2022). Department of Animal Husbandry and Dairying, Government of India.

- Indian Institute of Soil Science (IISS). (2021). Leaf Litter Contribution of Mahua to Soil Nutrient Cycling and Carbon Dynamics. Bhopal, India.

- World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF). (2019). Livestock-Forest Interactions in Agroecological Landscapes: The Role of Mahua and Other Multipurpose Trees. Nairobi, Kenya.

- ICAR Feed Resource Bulletin. (2021). Composition and Energy Profile of Non-Conventional Feed Ingredients in India. ICAR-NIANP, Bengaluru.

- Indian Institute of Soil Science (IISS). (2020). Role of Tree-Based Systems in Enhancing Soil Health and Water Retention. Bhopal, India.