Understanding the Science Behind India’s Traditional Flour Processing

Jai Jungle: Science Behind Tradition

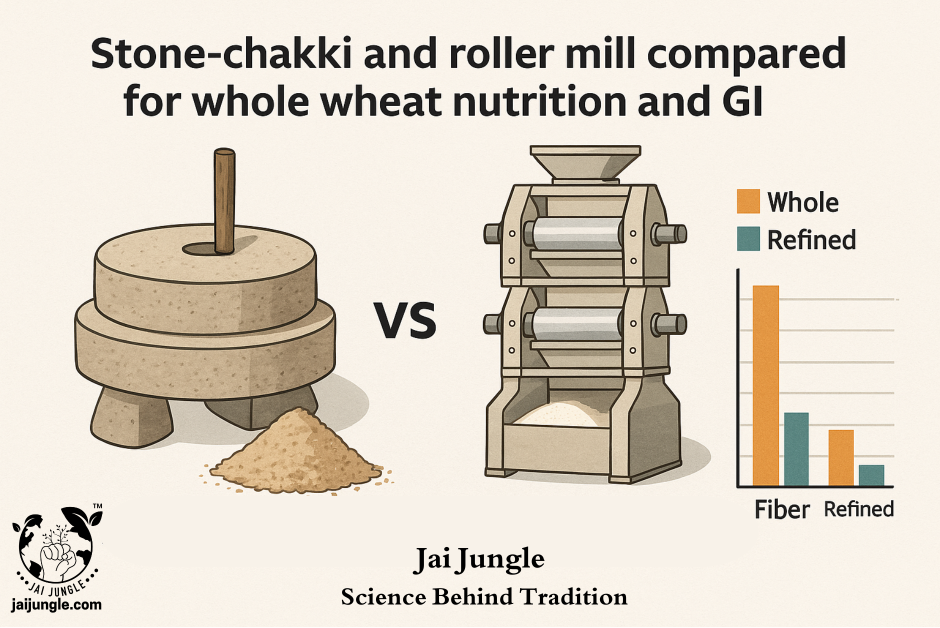

For centuries, Indian homes have relied on the slow, rhythmic grinding of the hand-operated home chakki — a small stone mill turned patiently by hand. It wasn’t just a kitchen tool; it was a way to preserve freshness, aroma, and nutrition. With industrialization, modern roller mills took over — fast, efficient, and uniform.

But what do we really lose or gain in this shift? Does the humble hand chakki truly offer superior nutrition, or is it nostalgia speaking? Let’s examine what science says about nutrients, heat, starch, and the overall food quality.

1. Two Contrasting Systems

1.1 Hand-Operated Traditional Chakki

The home chakki uses two circular stone plates that rotate slowly against each other. The top stone moves manually, crushing the grain between the stones by slow compression and friction.

Because of this gentle action, the entire grain — bran, germ, and endosperm — is ground together into a natural wholegrain flour.

Crucially, the process remains cool. Since it’s manually operated, the temperature rarely exceeds 35–45°C — significantly lower than in any motorized or industrial mill.

This is why traditional hand chakkis are considered a form of “cold processing.”

At such low temperatures, heat-sensitive nutrients like Vitamin E, Omega-3 fatty acids, and enzymes remain intact, making the flour rich, aromatic, and nutritionally alive.

The slow grinding also gives a slightly uneven texture — some fine particles, some coarser — which naturally reduces the glycemic response and adds a wholesome mouthfeel to chapatis.

1.2 Modern Roller Milling

Modern roller mills operate through a series of metal rollers and sifters that separate the grain’s parts: endosperm, bran, and germ.

The process happens in multiple stages at moderate temperatures (30–40°C). Roller milling produces a fine, uniform flour, ideal for large-scale bread and bakery production.

However, the main limitation is refinement. Most commercial mills remove the bran and germ to produce white flour (maida), which is lower in fiber, minerals, and vitamins.

Whole-wheat roller flour (where all parts are recombined) can achieve similar nutrition to hand-chakki flour — but such products are rare in industrial practice.

2. The Real Difference — Wholegrain vs Refined

Scientific studies agree that the major nutritional gap is not stone vs roller, but whole vs refined.

| Component | Whole Wheat (Chakki/Wholegrain) | Refined (Maida) | Nutrient Loss (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fiber | 11–12 g/100 g | 0.5–1 g/100 g | ~90 % |

| Iron | 4–5 mg/100 g | 2 mg/100 g | ~50 % |

| Magnesium | 120 mg/100 g | 30 mg/100 g | ~75 % |

| Vitamin E | 1.5–2 mg/100 g | Nearly zero | ~90 % |

| Vitamin B₁ | 0.4 mg/100 g | 0.06 mg/100 g | ~80 % |

Traditional hand-chakki flour naturally retains these nutrients because nothing is removed — every part of the grain remains.

Refined roller flour, by contrast, loses 50–80 % of minerals and nearly all Vitamin E and fiber.

3. Temperature, Oils, and Vitamins

The Cooling Advantage

In a hand-operated chakki, the slow motion and intermittent grinding prevent significant heat buildup.

Studies that reported flour temperatures around 85–90 °C were based on motorized commercial stone mills, not manual home chakkis.

In manual grinding, flour temperature remains under 45 °C — not enough to degrade vitamins or lipids.

This means hand chakki flour preserves:

- Vitamin E (tocopherol) — an antioxidant that prevents rancidity.

- Linolenic acid (Omega-3 fatty acid) — sensitive to heat and oxidation.

- Active enzymes — that help with dough fermentation and digestion.

The result is a flour that’s chemically stable and nutritionally dense, even without refrigeration, when consumed fresh.

Roller Milling

Roller mills, though faster, also operate relatively cool (~35 °C), but they remove germ oil to extend shelf life.

That’s why industrial flour may remain fresh longer — yet lacks the natural oils and flavor of hand-ground flour.

4. Starch Damage, Water Absorption & Chapati Texture

Grinding in the hand chakki crushes starch granules gently. The damaged starch content is moderate (typically 6–9 %), enough to improve water absorption and softness, without excess enzymatic breakdown.

This gives the dough:

- Higher water-holding capacity,

- Better puffing during cooking,

- A naturally soft texture that stays fresh longer.

By comparison, roller-milled flour has less damaged starch (4–6 %), producing firmer dough and slightly tighter rotis unless hydration is increased.

In short:

- Hand chakki = soft, moist chapati (natural water retention).

- Roller flour = tighter dough (needs +10–15 % extra water).

5. Particle Size and Glycemic Index (GI)

One subtle but important factor is particle size.

Hand chakki flour is slightly coarser and more varied — some small, some large particles — while roller-milled flour is uniformly fine.

Research (Reynolds et al., 2020) shows that coarse wholegrain flour can lower post-meal blood glucose by up to 20 %, because larger particles slow down starch digestion.

Thus, hand chakki flour tends to have a mildly lower glycemic index, especially when eaten as chapati or phulka.

Still, both remain low-GI foods when wholegrain is used. The key factor is not the mill type but the presence of intact bran and fiber.

6. Flavor, Aroma, and Freshness

Hand-chakki flour is instantly recognizable by its warm, nutty aroma and rich color.

Because the germ oil stays embedded in the flour, it has a naturally sweet and earthy taste.

Freshly ground flour also has active enzymes that continue to enhance aroma during cooking.

However, these same oils make hand-chakki flour more perishable.

After about 4–6 weeks, especially in warm climates, the oil can oxidize and produce a faint bitter smell.

That’s why traditional households always milled small quantities — “fresh flour every month” wasn’t just a saying, it was food science.

7. Health Implications

- Fiber and Digestion: Wholegrain flour supports gut health and regular digestion.

- Blood Sugar Control: Replacing refined flour with wholegrain chakki flour lowers diabetes risk.

- Heart Health: Natural germ oils and antioxidants in unrefined flour improve lipid balance.

- Satiety and Weight: Higher fiber creates fullness, helping with appetite control.

In an Indian clinical trial (Malik et al., 2019), substituting refined grains with whole grains reduced type-2 diabetes risk by 13 %.

Thus, even a simple shift — from roller-refined to hand-chakki wholegrain — can have measurable public health benefits.

8. Practical Guidance for Home Users

- Choose wholegrain wheat — the key is to retain bran and germ.

- Grind small batches (2–4 kg at a time) to preserve freshness.

- Keep chakki speed slow — avoid motor attachments that generate heat.

- Avoid sifting — never remove the coarse bran; that’s where nutrients live.

- Store in airtight containers in a cool, dark place; refrigerate if humid.

- For soft rotis: Rest the dough 20–30 minutes; add a few drops of oil.

- Blend varieties: Mixing coarse and fine wheat gives balanced texture and GI.

- Fermented recipes: Using hand-chakki flour in dosa or sourdough enhances nutrient absorption.

9. Tradition Meets Science

The gharalu hand chakki was slow, effortful, and intimate — but it was also scientifically smart.

Its low-speed, low-heat milling preserved natural oils and micronutrients long before “cold-pressed” or “stone-ground” became marketing terms.

Today, modern roller mills offer efficiency, hygiene, and uniformity — but at the cost of some natural diversity and freshness.

The ideal future may blend both: the purity of tradition and the precision of modern science.

10. Key Takeaways

| Aspect | Hand-Operated Home Chakki | Modern Roller Mill |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 35–45 °C (cool) | 30–40 °C |

| Grain parts | All intact (wholegrain) | Often refined |

| Starch damage | Moderate (soft dough) | Low |

| Particle size | Varied (coarse + fine) | Uniform, fine |

| Vitamins E & Omega-3 | Preserved | Often lost (if refined) |

| Texture | Soft, pliable chapati | Tighter dough |

| Shelf life | 4–6 weeks | Longer (if refined) |

| GI impact | Slightly lower | Similar if wholegrain |

11. Conclusion

When it comes to health and taste, the hand chakki still holds its ground.

Its gentle, cool milling protects sensitive nutrients, yields soft and aromatic flour, and preserves the character of the grain.

Roller mills have their place — for consistency and scale — but for daily home use, freshly ground flour from a hand-operated chakki remains nutritionally superior and culturally irreplaceable.

It’s not nostalgia — it’s nutritional logic rediscovered.

References

- Carcea M. et al. (2020). Stone Milling versus Roller Milling in Soft Wheat: Influence on Products Composition. Foods, 9(1):3.

- Prabhasankar P. & Rao P.H. (2001). Effect of Different Milling Methods on Chemical Composition of Whole Wheat Flour. Eur. Food Res. Technol., 213:465–469.

- Reynolds A.N. et al. (2020). Wholegrain Particle Size Influences Postprandial Glycemia in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care, 43(2):476–479.

- Miller Jones J. et al. (2015). Nutritional Impacts of Different Whole Grain Milling Techniques: A Review. Cereal Foods World, 60(3):130–139.

- Malik V.S. et al. (2019). Substituting Brown Rice for White Rice on Diabetes Risk Factors in India. Br. J. Nutr., 121(12):1389–1397.

- FSSAI (2020). Food Safety and Standards (Cereals and Cereal Products Regulations).