Why bats, moths and bees matter—and how small changes protect both forests and livelihoods

Introduction: The night shift that feeds a village

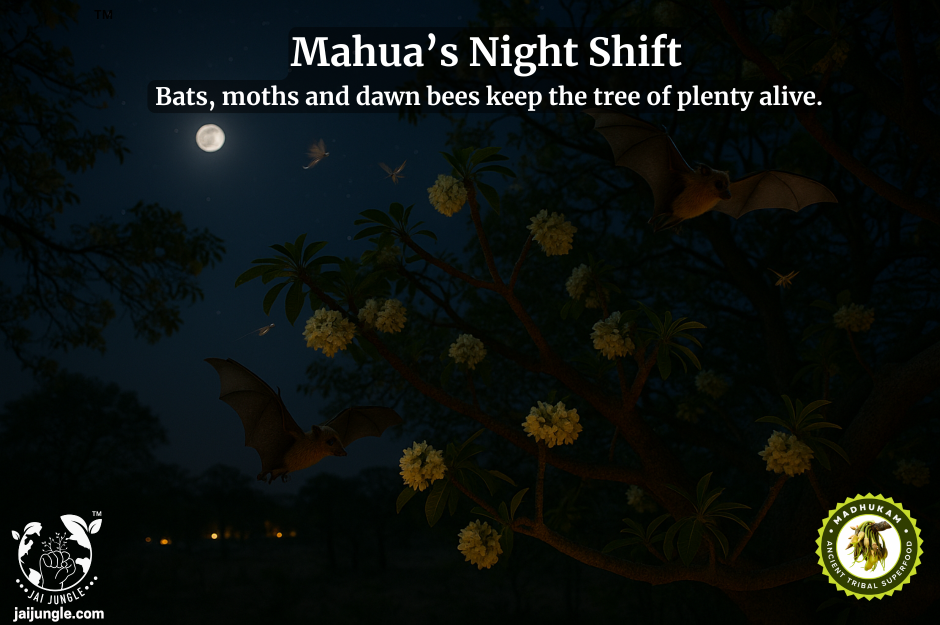

On a warm April evening in central India, the Mahua tree opens for business just as the day quietens. Flowers loosen from tight buds, scent builds in the air, and a night workforce arrives: fruit bats on direct flights between groves, moths tracing invisible odour plumes, and—in the cool of early morning—bees finishing the night’s work. What happens in these hours is not folklore; it is pollination, the silent logistics that decides how many fruits set, how viable seeds are, and—indirectly—how resilient the wider ecosystem remains. Ecologists have long noted that Mahua’s night-blooming traits—strong scent, pale blossoms, abundant nectar, and exposed inflorescences—fit the classic profile of plants that rely heavily on bats, with moths and other visitors contributing locally.Mongabay-India+1

In many Mahua landscapes, however, the night shift is increasingly disturbed. Ground burns to clear litter for collection, flashlights and yard lights blazing through the evening, diesel pumps chugging, smoke and ash drifting across canopies—each adds friction to a delicate system. This article explains how Mahua is pollinated, why night matters, how light and smoke interfere, and what small, practical steps villages can take to keep pollinators returning—linking ecological sense with everyday benefits for farmers and forest dwellers.

1) The flower that works after dark

Night-blooming design. Mahua (commonly Madhuca longifolia) opens and sheds many of its flowers around dusk and at night during the hot-dry season. Pale, fleshy corollas, a rich fermenting perfume, and robust nectar rewards indicate adaptation to nocturnal vertebrate pollinators—particularly fruit bats—while also supporting nocturnal insects. These traits are widely associated with chiropterophily (bat pollination) across many tropical plant families.PMC

Who visits, typically? Field observations and reportage from Indian ecologists highlight fruit bats as primary visitors to Mahua, with moths frequently recorded at night and bees foraging at dawn as the last nectar and pollen remain. Evidence from Mahua’s close relatives in the Sapotaceae (e.g., Madhuca spp. and Palaquium) also documents bat and bee visitation in this group.Mongabay-India+1

Why bats matter here. Bats travel long distances, move pollen between widely spaced trees, and carry substantial loads of pollen on fur—patterns consistent with bat-pollinated plants worldwide. In bat-pollination systems, copious pollen and nectar, sturdy blooms and open architecture are common—and Mahua checks these boxes.Chicago Journals+1

2) Moths, bees and the morning hand-off

Moths are the night’s other quiet workforce. Drawn by scent and nectar, they move between blossoms, transferring pollen as they feed. Scientific reviews show that artificial light at night (ALAN) can disorient moths, reduce their ability to navigate, and lower pollination rates at lit sites—a problem for any nocturnally serviced plant community.PMC+1

At first light, bees often appear on Mahua to take what remains. In some locales they may contribute to pollination or simply clean up nectar and pollen, depending on timing and floral condition. The combined effort—bats and moths by night, bees at dawn—underpins fruiting in many stands. (Within the Madhuca genus, mixed visitation and multiple pollination modes have been recorded in congeners, reinforcing the idea that Mahua benefits from a diverse pollinator community.)IJAR+1

3) Why light, smoke and ground burns interrupt the night economy

Light at night (ALAN). Bright white and blue-rich LEDs dominate rural lighting. Studies demonstrate that ALAN can delay or suppress nocturnal activity, trap insects near lamps, and reduce pollinator visits to nearby flowers; it also alters bat flight behaviour along lit edges. For villages, the actionable insight is simple: excess light equals fewer nocturnal pollinators where it matters.PMC+2PMC+2

Smoke and heat pulses. Ground burns create hot, smoky microclimates around trunks and understorey. While controlled fire has roles in some ecosystems, repeated burns in Indian dry forests are linked to loss of litter, simplified understorey structure and short-term faunal disturbances—conditions unlikely to favour nocturnal pollinator activity near canopies. (National and scholarly reviews on Indian dry forests emphasise prevention, noting biodiversity and ecosystem-service costs of frequent burns.)opus.bibliothek.uni-augsburg.de+1

Direct disturbance at the tree. Shaking branches, beating sticks, loud engines and bright torches during peak pollination hours (dusk–midnight) interrupt foraging. Even brief disturbance can redirect bat flight paths and moth movement for the night—lost visits that cannot be recovered once flowers fall.

4) What we know about Mahua and bats (and why it makes sense)

Globally, bat-pollinated plants follow a recognisable pattern: night opening, strong scent, pale/cream flowers, ample nectar, sturdy floral parts, pendant or exposed positioning. Mahua lines up neatly with these features, and Indian naturalists frequently report fruit bats working Mahua canopies in season. Reviews tracing the evolution and mechanics of bat pollination explain why bats are excellent cross-pollinators for large, scattered trees like Mahua: they commute widely, tolerate heat, and can deliver pollen across distances that many insects do not routinely bridge.PMC

Evidence from India and neighbouring regions continues to build the case: Mahua and related Sapotaceae receive bat visits, sometimes alongside bees and birds; morphological and nectar traits support chiropterophily; and field accounts document fur-borne pollen transfer in bat visits.Mongabay-India+2NUS LKCNHM+2

5) A night in the grove: a narrative from central India

Collectors describe a rhythm they recognise from childhood. At dusk, first bats appear as silhouettes, circling and landing briefly, faces buried in blossoms. Minutes later, moths flicker through torchlit dust like sparks, then merge into the dark, invisible but working. At dawn, bees arrive, quiet but businesslike, picking the last nectar threads before heat closes the window. Villagers also describe the nights when visitors fail: a neighbour burns to clear a floor; smoke pools under the canopy; lamps stay on all night by the cowshed; a generator rattles; the breeze turns. The difference is visible the next morning—fewer fresh fruits developing, more dropped flowers.

This narrative is not a controlled study—but it aligns with the best-available science on ALAN and nocturnal pollinators and with observations on fire-altered understoreys in Indian dry forests.PMC+2PMC+2

6) Small, non-technical ways to keep Mahua pollinator-friendly

The aim is not to enforce rules; it is to make nights friendlier for the workers Mahua relies on. These steps are all low-cost and commonsense.

6.1 Light the village, darken the grove

- Switch off yard lights around Mahua trees from dusk to midnight during peak bloom.

- If light is essential, use warm (amber) lamps and down-shields; avoid blue-white LEDs that scatter widely.

- Place necessary lights behind structures so canopies stay dark, and fit motion sensors where feasible.

These actions directly address the mechanisms by which ALAN reduces nocturnal pollination.PMC+1

6.2 Keep smoke and flame away from canopies

- Skip ground burns beneath Mahua during the season; they remove litter, simplify habitat, and create hot, smoky air columns at the very time bats and moths fly. National guidance on forest fires already prioritises prevention; community practice simply needs to match it.Digital Sansad

- If clean floors are important for collection, use non-burn alternatives (elevated collection nets, careful raking hours away from peak pollination). Nets, in particular, eliminate ignition sources while keeping flowers clean—a win for pollination and for livelihoods (as discussed in our fire-prevention article).

6.3 Quiet hours for the night shift

- Avoid heavy disturbance (branch beating, loud engines, floodlighting) from dusk to midnight near trees in bloom.

- Plan necessary activity for late night or early morning once peak visitation subsides.

6.4 Keep nectar corridors intact

- Maintain hedgerows, native shrubs and understorey near Mahua stands—these offer waypoints for moths and resting cover for bats.

- Retain small water points (earthen containers, shaded troughs). Even brief sips can extend foraging time in hot, dry nights.

6.5 Pesticides and aerosols

- Avoid broad-spectrum sprays on or near Mahua during bloom; if absolutely necessary for nearby crops, time applications for midday when nocturnal visitors are absent and wind is low. (General good practice; specific crop protection is beyond this article.)

None of these measures are complicated. Together they nudge the night back towards conditions Mahua evolved with—low light, low smoke, rich scent trails, and open air.

7) Why this is not just “eco”—it is good economics

Mahua collection depends on predictable flowering and fruit/seed development that follows pollination. When pollination fails, flowers drop, fruit sets poorly, and seed yields can be erratic. Villagers cannot manage bats and moths directly—but they can remove barriers to their work. A few dark, quiet, smoke-free hours cost little and improve the odds that the night workforce does what it has always done.

From a forest-management perspective, the same steps reduce ignition pressure, protect soil organic matter (by not burning litter), and lower patrol stress. In practice, pollinator-friendly villages are often fire-sensible villages—because they already value dark, calm nights and understand the quiet economy of flowers.

8) Mahua in a changing countryside: risks and resilience

Rural electrification brings benefits, but also more ALAN near groves; LEDs are cheap and bright, spilling light through canopies. Heat and drought alter flowering windows, sometimes concentrating bloom into narrower periods—which makes each night of successful pollination matter more. The simplest resilience strategy is also the cheapest: keep canopies dark and undisturbed on key nights, and eliminate fire under and around trees. Research on nocturnal pollinators consistently warns that ALAN reduces movement and visitation; emerging policy on forest fires emphasises prevention and community stewardship. Aligning village practice with these signals is both ecologically sound and practical.PMC+2PMC+2

9) What communities already observe

Across Mahua villages, people name the bats that “taste” the flowers, remark on the sweet smell that “calls them”, and tell stories of quiet, dark groves yielding better. They also notice how lamps, smoke, and noise scatter the night traffic. These observations—while anecdotal—fit the broader record on bat-pollinated plants and ALAN-sensitive nocturnal insects. Where villages switch off lights and skip burns, the night feels alive again; and in the weeks that follow, trees look heavier with developing fruit.

10) Frequently asked questions

Is Mahua only bat-pollinated?

Mahua shows many bat-pollination traits, and bats are widely reported as key visitors. But other animals—moths and bees among them—also visit, and congeners show mixed pollination. This diversity is a strength: multiple pollinators share the workload across the long, hot nights of the season.Mongabay-India+1

Do village lights really matter that much?

Yes. Evidence shows ALAN can reduce nocturnal insect visitation, trap or disorient moths, and shift bat movement along lit corridors. Shielding, warming the colour of light, and switching off unnecessary lamps during bloom directly improves the pollination environment.PMC+1

What’s wrong with a quick ground burn?

Beyond fire escape risks, burns strip litter and simplify understorey right when nocturnal visitors need cool, humid, structured air layers and safe movement. National fire guidance prioritises prevention for good reason.Digital Sansad

We see fewer bats than before—what can we do?

Keep canopies dark and quiet; avoid burns; maintain tall roost trees and hedgerows; protect water points. None of this guarantees numbers, but it removes barriers and supports recovery.

Is there hard, India-specific proof for every grove?

Mahua occurs across varied landscapes. The direction of evidence—from Mahua/relatives, from global bat-pollination science, and from ALAN research on nocturnal insects—is consistent. Local monitoring (flower visits observed, fruit set trends, fewer burns/lights) can make the case tree by tree.

11) A small intervention with a wide ripple

In the previous article we showed how scientific collection nets cut the incentive to burn. Here, the pollination perspective adds another reason to keep nights dark and clean. Switch off the lamp, save the litter, skip the fire: each of these is small, no-cost or low-cost, and compatible with daily life. Together they strengthen Mahua’s night ecology, support better fruiting, and reduce fire and management stress in the hottest, driest months.

Mahua is often called the “tree of plenty”. Its plenty is the product of countless, ordinary nights in which plants and animals meet as they have for millennia. Keeping those nights welcoming is not a grand programme; it is simply good sense—and good stewardship.

References / further reading

- Fleming, T. H., Geiselman, C., & Kress, W. J. (2009). The evolution of bat pollination: a phylogenetic perspective. Biotropica, 41(3), 399–418. (Open-access review on plant–bat adaptations.) PMC

- Owens, A. C. S., & Lewis, S. M. (2018). The impact of artificial light at night on nocturnal insects. Animal Conservation, 21(6), 1–10. (Open-access synthesis via PMC.) PMC

- MacGregor, C. J., et al. (2014). Pollination by nocturnal Lepidoptera, and the effects of light pollution. Ecological Entomology (review; open-access via PMC). PMC

- Briolat, E. S., et al. (2021). Artificial nighttime lighting impacts visual ecology (moth behaviour and predation risk pathways). Nature Communications. Nature

- Mongabay India (2018). Heaven is where there are Mahua trees—and their bat friends. (Field reportage on Mahua traits and bat visitation in India.) Mongabay-India

- Phang, A. (2023). Novel observations of chiropterophily in Palaquium (cites Madhuca genus as bat-/bee-visited; Sapotaceae context). Nature in Singapore. NUS LKCNHM

- Nathan, et al. (c. 2009). Bat foraging strategies and pollination of Madhuca latifolia in Southern India. (ResearchGate abstract; bat visitation to Mahua.) ResearchGate

- MoEFCC (2018, 2024). National Action Plan on Forest Fire (NAPFF)—Parliament briefings and scheme notes (prevention focus). Digital Sansad+1

- Schmerbeck, J., Kohli, A., & Seeland, K. (2015). Ecosystem services and forest fires in India—context and policy implications. Environmental Management (dry-forest review; India). ScienceDirect+1