Introduction: The Unsung Pillars of the Mahua Journey

The story of Mahua (Madhuca longifolia) is not merely about a forest tree — it’s about the women whose hands sustain the entire ecosystem around it.

Across India’s Mahua belts — from Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Odisha to Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra — Mahua represents both a seasonal harvest and a living rhythm of community life.

The value chain, from pre-dawn flower collection to the final sale in local markets, is shaped largely by women.

Understanding these gender roles is essential to appreciating Mahua not just as a Non-Timber Forest Produce (NTFP), but as a gendered forest economy, where women’s invisible labor, ecological knowledge, and decision-making power sustain the resource itself.

Women as Primary Collectors: Forest at Dawn

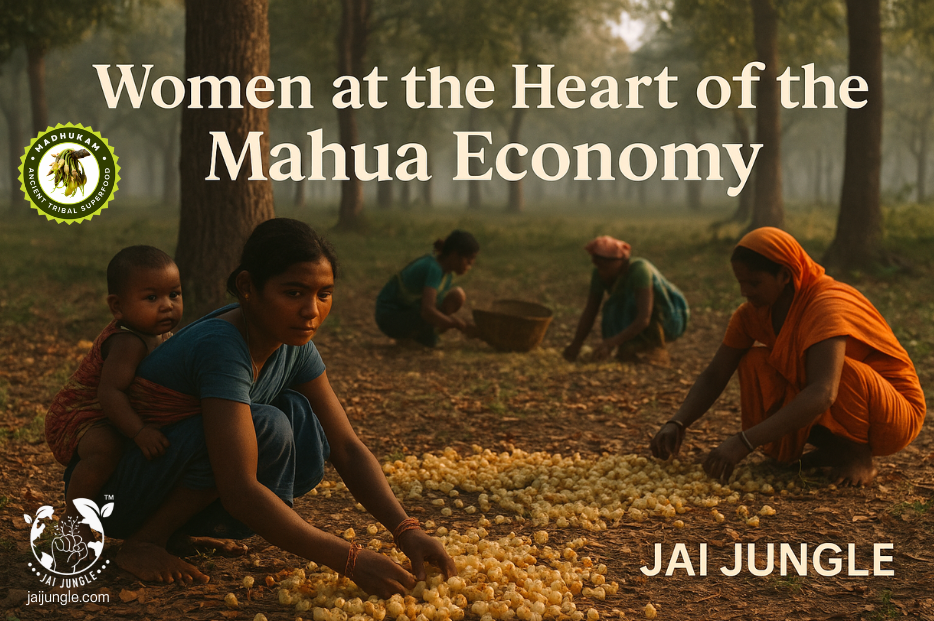

Every Mahua season, as the night sky fades between March and May, thousands of tribal women begin their day before sunrise.

At around 4 a.m., golden Mahua flowers start to fall silently to the forest floor.

By 5 a.m., women carrying bamboo baskets walk in small groups toward the groves, their children often tagging along.

This early-morning scene — women stooping under trees, hands sweeping through dew-laden leaves — is the living heartbeat of rural India’s forest economy.

Collection is time-sensitive and physically demanding.

The flowers must be gathered quickly before the sun grows hot or animals disturb them.

A single woman may spend 6–8 hours collecting 20–25 kilograms of Mahua, bending thousands of times.

In many areas, infants are tied to their mothers’ backs or laid in makeshift cradles beneath the trees.

Mahua collection happens alongside caregiving, showing how women merge household and livelihood seamlessly within forest space.

As one tribal woman from Kandhamal (Odisha) told 101Reporters (2022):

“My husband goes for daily labor. But the jungle is ours — Mahua, tendu, sal leaves — that’s our world.”

The sentiment echoes across central India: the forest is women’s domain, where economic activity and social life intersect.

Cultural and Emotional Dimensions: The Forest as a Women’s Space

Beyond economics, Mahua collection is also a social and cultural act.

For tribal groups such as the Baiga, Oraon, Korwa, Gond, and Kondh, the Mahua season is both labor and festival.

Women sing Mahua geet — folk songs of rain, fertility, and sisterhood — while collecting flowers.

Elders recall that the first batch of blossoms is traditionally offered to the village deity or kul devi, symbolizing respect for the forest that feeds them.

This ritual is ecological gratitude encoded in culture.

The forest during Mahua season becomes a women-only workspace, filled with laughter, shared stories, and intergenerational teaching.

Older women show younger ones how to identify a fresh flower, how to shade-dry it, and how to test for spoilage by smell.

Knowledge flows orally — no manuals, no machines — just centuries of lived expertise.

This collective work strengthens solidarity and social bonds among women — an often-overlooked dimension of gendered forest economies.

Economic Backbone: Women as Breadwinners

Mahua income is vital for rural survival.

Studies (101Reporters, 2022) show that up to 30 percent of a tribal household’s annual income comes from the sale of Mahua flowers.

However, field observations by the Jai Jungle team (Samarth Jain Report, Bijapur 2025) reveal that in deeper tribal belts — where formal wage labor and market access remain limited — this share can rise dramatically to 80–90 percent of household income.

In remote corners of Jashpur, Bastar, Dantewada, and Bijapur, Mahua is the true financial lifeline.

In several weekly markets of Dantewada and Bijapur, Mahua even functions as a barter commodity — exchanged directly for rice, oil, or salt.

As documented by the Jai Jungle field study, villagers refer to Mahua as their “living currency.”

This seasonal income bridges the “lean months” before the next agricultural harvest.

Women typically control this income directly, deciding whether to spend it on education, health, or provisions.

In emergencies — a child’s illness or a marriage — Mahua becomes the household’s only liquid asset.

Thus, Mahua is not merely a forest resource; it is women’s informal bank account, replenished by their daily labor and ecological stewardship.

Processing and Production: Transforming Flowers into Value

Once collected, the next stage — drying and preservation — again rests in women’s hands.

They spread the flowers on straw mats or bamboo platforms, turning them repeatedly under the sun to prevent mold.

They can sense with their fingertips whether the flower is too damp or perfectly crisp — a skill born of generations of observation.

When dried, flowers are stored in jute sacks or earthen pots.

Earlier, excise rules made even this simple act risky; police often raided homes if stockpiles were suspected for liquor brewing.

Women recall hiding their sacks under grain bins to avoid confiscation — yet they persisted.

Value Addition: From Flowers to Food

Over the last decade, tribal women have begun turning Mahua into high-value food products.

Self-help groups (SHGs) now produce Mahua laddoos, jaggery, candies, and syrups, along with herbal teas and wellness blends.

In Telangana, a Krishi Vigyan Kendra program trained women to make Mahua laddoos, raising their seasonal income by nearly 80 percent.

In Chhattisgarh, the Jai Jungle Farmers Producer Company (FPC) has advanced this model further —

training more than 3,000 tribal women in hygienic drying, grading, packaging, and branding Mahua as a modern, preservative-free superfood.

These efforts have transformed women from mere collectors into entrepreneurs and stakeholders, ensuring profits flow back to their communities.

Market Realities: Women Work, Men Trade

Despite their central role, women face major barriers at the selling stage.

Most carry 20–30 kg headloads of dried Mahua to weekly haats (markets), walking several kilometers over uneven terrain.

Once there, they confront a male-dominated trading space where middlemen dictate prices.

Unable to carry unsold loads home, women are often forced to accept whatever price is offered.

In surplus years, prices can fall to ₹15–₹20 per kg — barely covering the day’s costs.

This reveals a gendered paradox:

women perform nearly 90 percent of the labor in the Mahua economy yet capture less than half its value.

Men dominate as traders, transporters, and license holders.

Until recently, excise regulations even required male intermediaries for bulk sales, formally excluding women from the trade they sustain.

Invisible Knowledge: The Science Within Tradition

Economic statistics rarely capture the intellectual labor women invest.

Each collector can identify, by sight and scent, whether a flower has fermented or dried correctly.

They know which trees bloom early, which forest patches yield the sweetest blossoms, and how to protect flowers from insects using smoke or neem leaves.

They even use Mahua strategically in animal care — mixing small quantities with cattle feed during lean months for nutrition.

These micro-practices form an unwritten science of sustainable forest management that has evolved over centuries.

Recognizing, documenting, and rewarding such ecological intelligence is critical for the long-term sustainability of Mahua landscapes.

Empowerment Through Cooperatives and Producer Companies

Across central India, a quiet transformation is taking root.

Women-led cooperatives and producer companies are gradually shifting the balance of power.

In Chhattisgarh, the Jai Jungle Farmers Producer Company represents this new paradigm.

Here, women not only collect Mahua but also manage processing, packaging, and sales.

They hold shares, vote on business decisions, and determine product pricing collectively.

Under this model, tribal women have evolved from daily wage earners into equity holders of their own enterprise.

Each packaged product — Mahua Nectar, ForestGold Vanyaprash, Mahua Infusion Tea — carries the story of these women:

forest gatherers turned product developers, custodians turned innovators.

This shift reflects a larger truth — empowering women in the Mahua value chain empowers the forest itself.

The Social Ripple: Beyond Economics

When women gain income and agency through Mahua, the benefits ripple far beyond the household.

- Nutrition improves: Mahua earnings bring vegetables, grains, and school meals.

- Education expands: daughters stay in school longer.

- Leadership grows: SHG-active women begin attending gram-sabhas and local governance meetings.

- Health access rises: steady income enables families to seek medical care instead of relying solely on forest remedies.

In this way, Mahua strengthens entire communities — socially, financially, and ecologically.

Policy and Technological Pathways Forward

Empowering women in the Mahua value chain requires multi-layered action:

1 | Policy Reform

Simplify excise laws and recognize Mahua as a nutritional forest produce, not merely a liquor raw material.

Introduce Minimum Support Prices (MSP) for NTFPs like Mahua to prevent market exploitation.

2 | Technology & Tools

Provide food-grade collection nets, gloves, and solar dryers to reduce strain and enhance quality.

Jai Jungle’s pilot projects with net-based collection have shown a 40 percent increase in yield and cleaner flowers — proof that simple innovations can revolutionize livelihoods.

3 | Market Linkages

Connect women producers directly with institutional and digital markets — tribal marts, e-commerce, and fair-trade buyers — ensuring equitable pricing.

4 | Skill & Capacity Building

Continuous training in hygiene, bookkeeping, digital literacy, and food safety standards empowers women to move from the informal to the formal economy.

When women learn to brand and market their products, they gain both dignity and control.

Reflections: The Mahua Grove as a Microcosm of Gender Justice

In many ways, a Mahua grove mirrors society itself.

Its shade shelters women, children, and life — yet it demands care, patience, and cooperation to thrive.

The women who wake before dawn to collect fallen flowers are not just laborers; they are custodians of biodiversity and culture.

Their contributions align perfectly with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals:

- SDG 5 — Gender Equality

- SDG 15 — Life on Land

- SDG 8 — Decent Work and Economic Growth

Recognizing women as forest managers and entrepreneurs makes both the ecosystem and the economy stronger.

Women, Forests, and the Future of Mahua

From forest floor to packaged product, Mahua’s journey tells a deeper story —

of women who have long been the unseen backbone of India’s forest economy.

They rise before sunrise, balance infants on hips, carry 30-kg baskets, and turn fragile flowers into family income.

They are the quiet economists of the forest — the lifeline of the Mahua value chain.

As the Jai Jungle model demonstrates, when these women receive recognition, training, and collective ownership, Mahua transforms —

from a seasonal livelihood into a year-round emblem of sustainable enterprise and women’s leadership.

Empowering the women of Mahua isn’t just moral justice —

it is the most practical route to ecological balance and economic equity across India’s forested regions.

🌿 Mahua thrives where women thrive.